The question returns to “How do we assemble the stimulus in a picture”. That is, it is well researched but poorly understood that the stimulus present in a picture cannot and must not be a “match” to “as measured” in front of a camera. Even though our mediums as bound to a closed domain, there is a plethora of other details within the picture that govern the rates of change etc.

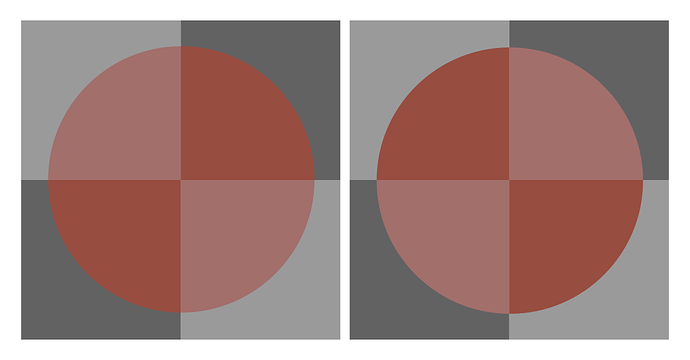

For example, as pointed out by @rawalanche, there is an incredibly strange purity continuum within a picture. While commonly referred to as “filmic roll off”, the rate of change of purity in a picture is incredibly complex. If the rate of change of the neurophysiological signal is “too fast” in a given receptive field, we cognize “otherness”, and the region will be cognized as a “boundary” instead of belonging (Gestalt) to the adjacent region. Worse, if there is little or no purity, the heuristics of picture decomposition also tends toward a “boundary”, as opposed to continuous “form”.

These devil’s instruments forward a very specific brand of stimulus analysis that falls under the banner of colourimetry. The idea that we can measure stimulus under an umbrella of trichromancy is fraught with nuance. I won’t wade into the waters, but the accepted orthodoxy of colourimetry’s territory is at least contested. I like this passage from the preface of Gilchrist’s Seeing Black and White:

The discovery of the detailed laws of Trichromacy is one of the great triumphs of visual science, although—as David Hubel noted— its practitioners study it with a passion that seems grossly out of proportion to its evolutionary importance.

The TL;DR is that there’s more going on in the articulation within a picture than deferring to some “origin” data. For example, think about an X-Ray picture. It’s most certainly not a simulacrum of the “as though we were standing there” for we’d not cognize anything, and we’d be suitably jeopardizing our retinas! Beyond that, how an X-Ray picture is sculpted relates to the meaning that the engineering seeks to communicate, and to whom the audience is who will be reading the text. Is the formed picture to encode a meaning of bone structure, of weakness in metals, or some other use? How we structure the picture is forever entwined with the meaning we seek to encode, and who will be decoding it.

Folks use words all the time, and use them poorly, inadequately, or improperly. “Tone” likely has an origin in the work of L. A. Jones, whilst working at… wait for it… Kodak!

We can look more recently to folks who slap the idea of “tone” onto curves or luminance mappers, and realize very quickly they all shit the bed pretty hard pretty rapidly in terms of the pictures formed. It is this phenomena that we ought to be attacking with force. In fact, I’d go so far as to say that all of this buffoonery gets it backwards; we aren’t mapping colourimetric tristimulus to a picture, but mapping from the neurophysiological cognition backwards. That is, we have to start with what we are trying to achieve in a given field articulation before we can figure out how. And this is where “tone”, or more specifically the erroneous and slippery definition stymies all attempts.

This is ultimately impossible, because the medium will always form the data into a picture. And even if we did this, we segue into the research papers I cited above; the colourimetry derived from a camera will inevitably lead to uncanny pictures in the cognitive sense. Folks will scream about “salmon coloured fire” or “meaty Caucasian skin”. This has been known since at least the 1950’s when researching photographic colour presentation, yet we seem to keep having to rediscover it time and time again. If you want evidence, read the three links I posted to the Pixls forum, which has folks more or less rehashing the same peculiarities present in the David MacAdam citation.

I would completely agree with the premise. However, none of this explains why. And that’s where we cannot avoid spelunking into the perplexing nature of how we arrive at meaningful interpretations of the neurophysiological signals.

It’s a region of thought that more than everyone here can engage with, knowing that zero people on the planet have any real clue. There’s some incredible wisdom out there, it just lives outside the scientism of “light” and the orthodoxy of colourimetry.

Dare I suggest that the craft folks who paint and render and create work are likely more in tune to discuss the matters than the dweebs making up scientism of plots and numbers. History cleaves this way if we look to the Gestaltists and folks who have explored colour cognition in the past. The number fornicators tend to poop the sheets here.

Folks who read a book have a visceral response to the encoded material, and it is a legitimate cognitive process. However, labelling the decoding as “appearing real life” is perhaps a dubious claim.

Please re-read the entire point I’ve been trying to make here; it doesn’t work this way! Caucasian skin, fires, and many, many, many other things look uncanny as hell when presented as “accurate” stimulus. This is why I waded into this discussion here, because I have a pretty damn good deal of respect for some of the minds around these parts that participate in threads like this.

The idea that an idealized picture is a perfect simulacrum of the stimulus present in front of the camera is false. Those citations above are the tip of a much deeper iceberg. The quotes from

Pixls are a straight line to the exact same phenomena. Further still, I have spoken with people who have done experiments along this axis, and they too back the claims up! Something else is going on in how we cognize pictures.

The best I can do is to draw awareness and suggest at least a degree of caution to avoid the belief that Judd, Plaza, and Balcom also assumed back in 1950 in their Condon Report.

Pictures are weird human artifacts.

![]()