I believe that by now the most-common modern sources are various forms of digital files – CAD and GIS files.

But in my particular area – which is “19th century” – very frequent use is made of “hand-drawn sources” including patent drawings, fire-insurance company maps, and builder’s blueprints. Realizing that these are not always comparable. (No, they positively are not: “they are what they are, and they’re all you’ve got.”)

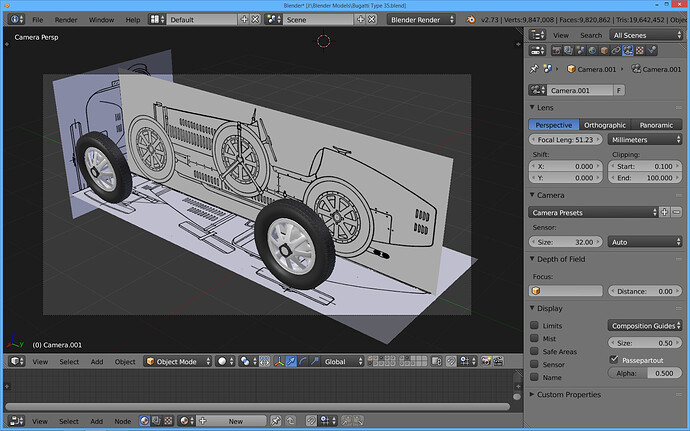

You also often find photographic records: builders would often take a photograph of everything they had built before shipping it to the customer, although they did not take them from the same location. A true photographic picture, unfortunately, is not a terribly-useful source because you don’t know where the photographer was, what lens he was using, and so on. It also makes a difference whether he was using a box camera, where the lens-plane and the film-plane must be parallel, or an “old-timey” view camera, where the photographer could and probably did put the two on different planes. *(Wiki it: “Scheimpflug Principle.” And: “orthographic projection.”)

In my situation I might just have an engraving from some old magazine, this being the only clue as to what the artifact once actually looked like when complete. If anyone ever bothered to record it in any other way – or, could have – the record no longer survives.

If you’re dealing with more recent artifacts – “firmly twentieth-century” – then you can usually find much more reference material. But since it was all hand-compiled you will also find a certain number of mistakes. (Consider the utterly- astounding(!!!) ongoing projects, all found right here, which are re-creating WW2 bombers, WW2 submarines, WW2 tanks and armaments, and WW2 rockets.)

Every situation is different, depending both upon the source-material that you are working with and the accuracy that you need to achieve. But, in my very-particular situation the most-important factor is relative scale. Since you can’t know exactly how big a particular [missing piece] was, you need to assess its relationship to the things which surround[ed] it as objectively as possible. Even if you know nothing else about the object, guess about its “bounding box,” and the dimensions of the “set” into which it is eventually to be situated. The rest is art.

I appreciate your detailed reply

I appreciate your detailed reply