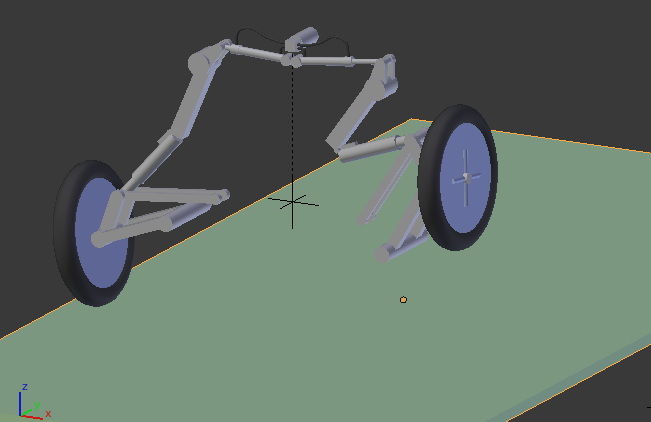

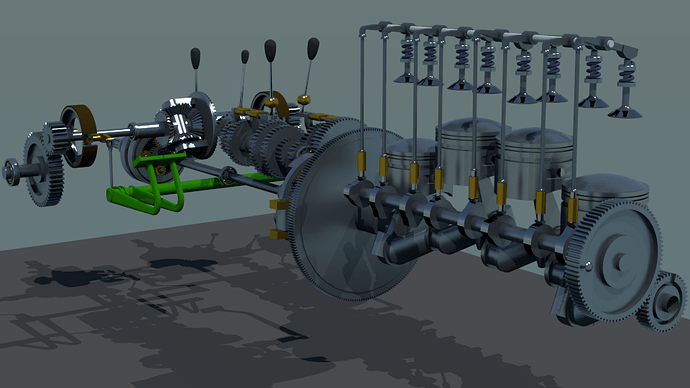

I rig a lot of steam-engines, industrial devices from the 19th Century, and stuff like that. There’s a “Rigging Mechanics” tutorial here which is, I think, “still one of the very best,” even though it is old now. There really are just a few key principles to keep in mind:

(1) “The cart leads the horse.”

Even though, in real life, the motion of a piston drives the wheel of a steam engine, when animating that engine the wheel turns on its own and the entire mechanism follows. Usually, this is a combination of track-to and point-to constraints, usually limited to certain axes, always operating in a local-coordinate space. Things that “move together,” such as a landing-gear and the doors that cover it, don’t have to be literally animated-as-one provided that their moves are appropriately synchronized somehow.

(2) “Empties are your Best Friend.”

In actual mechanisms, lines-of-force are sometimes expressed at funny angles, with other parts of the machine’s frame compelling that motion to follow a certain oblique line. When animating such things, use Empties. An Empty is simply an invsible point-in-space, but it is also an object that can be parented, and that can be constrained. It is “a point ‘over there’” that can be locked to “something ‘over here.’”

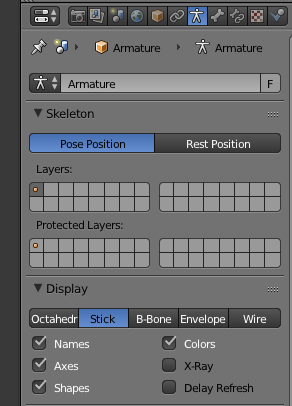

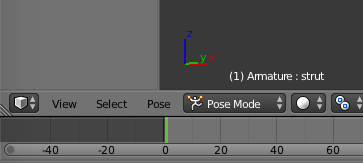

(3) “Consider how you will have to control it.”

For instance, if you’re using the NLA Editor, you’ll probably have to animate the movement of a “control bone” with “actions” causing other things to happen as a result of that. Consider what level-of-control you’ll need, and how the device’s movement will be specified in the finished shot. If the same mechanism will be used in many shots, you must plan-ahead for all of them. (It’s very easy to “get it perfect,” then realize that you can’t control it. koff koff :rolleyes: )

(4) “Animate/Rig no more than you have to, to ‘sell the shot.’”

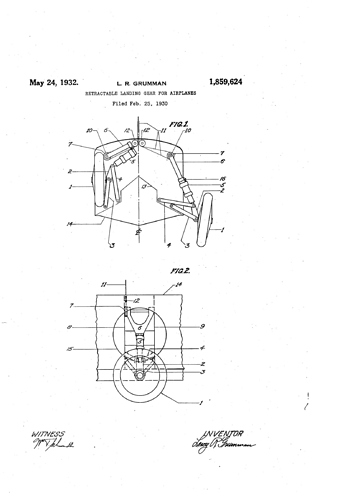

Unless this is an animation specifically meant to illustrate Mr. Grumman’s patent application, much of this mechanism is going to be concealed by cowling. (In any case, you choose where to put the camera.) Focus your attention only on what the audience can actually see, and consider omitting “the hard stuff” if there be any. Extreme close-ups of mechanical details, if there be any, can be treated as separate animations/rigs. “Cheat mercilessly.”

(5) “Take full advantage of my imagination, and of my understanding of ‘how things work.’”

Once you show me the device and show it starting to move, my imagination and my human-understanding of machinery will take over. For instance, “shot #1: the camera is mounted to the front of the airplane, and, as the plane ‘rotates’ into the air, the wheels start to fold.” CUT TO: “shot #2: medium-shot side-view of the airplane, taken from a following aircraft. The panels shut over the landing gear as the airplane banks away to the right.” The viewer doesn’t see it all, so you don’t have to animate what he doesn’t see; yet, he understands it all. The sequence shows exactly enough … meanwhile, the audience is scanning the skies behind the second shot, looking for that menacing German aircraft (which should appear in Shot #3). Pacing is everything.