A couple of weeks ago, I went to see ‘Oppenheimer’ (although a bit late to the party, I actually watched it twice, in the theater, I mean). Having seen the film, I went on to listen to the FXpodcast episode on it, as well as the FXshow episode on Barbie/Oppenheimer.

In the latter, right around the 1:00:00 mark (one hour mark), Mike Semour and the guys begin to talk something I’ve been personally kind of observing myself,- with some scepticism, to say the least - in recent years:

On those huge big budget Hollywood feature film productions where they do have very substantial VFX budgets and large amounts of FX-shots involved, there seems to be this hype around the idea of avoiding post-FX and avoiding especially CGI and trying to do as much as humanly possible in camera, one way or another.

And this is then often, - well at least in public, in promotional featurettes or interviews and such - being heralded as some kind of ‘the better, more real, more ground-truth way of doing things’, like if it was somehow an ellbow-grease way of making FX work in a true and honest way, in contrast to CGI being ‘the fake way of doing things’.

Now on a general note, personally, I think this notion of practical- vs. post-FX is largely complete nonsense (in so far as it’s not one versus the other). That’s also why it rubs me the wrong way, when I hear or read about people basically bragging with how they ‘keept it real’ on their filmset, so to speak, and didn’t use CGI and all that, as if that was an accomplishment in itself.

And especially as if practical FX work was actually ‘real’. Sure, it’s maybe tangible objects (miniatures etc.), but it’s a movie set, there’s no reality in a movie set.

Director Robert Zemeckis put it well in some FX Guide article from 2019:

There’s nothing more ridiculous than a closeup as far as the actor is concearned. He’s got a big piece of glass right in his face. You are looking at a piece of tape on a matte box. There are no other actors that you can see. Any fellow actors, also doing the scene, are 20 feet away, delivering their lines off camera. And then there’s a bunch of technicians, with their bellies hanging out, surrounding the camera and the actor or actress having to deliver the most emotional moments of the movie. It’s pretty ridiculous. And yet that’s when everyone says ‘look at that acting,- it’s just so real’, yet it’s being done in a completely unreal environment. Movies have always been technical. It’s a technical art form, nothing is real. It never has been.

- Robert Zemeckis, director

So what’s with this sort of hostility towards CGI, there seems to be floating around?

I will have to say, what is being done on something like a ‘Guardians of the Galaxy’ movie, where they have a the whole cast in performance-capture gear on a soundstage surrounded by greenscreens, and in post they’ll retarget one to be a two-foot tall raccoon and one to be a,- whatever - 20 foot tall whatever it is, well, I personally think that is taking it a bit far. And before you ask, no, I never watch such superhero-crap, I’m not the most competent to judge the actual onscreen final outcome.

Well, OK, I’m going to be honest here, I have watched like two or three movies of the genre, mostly when it wasn’t my decision what to watch (the first X-Men movie, that I actually watched on my own decision, ‘Green Lantern’, I guess ‘Sin City’ kind of falls into the genre too).

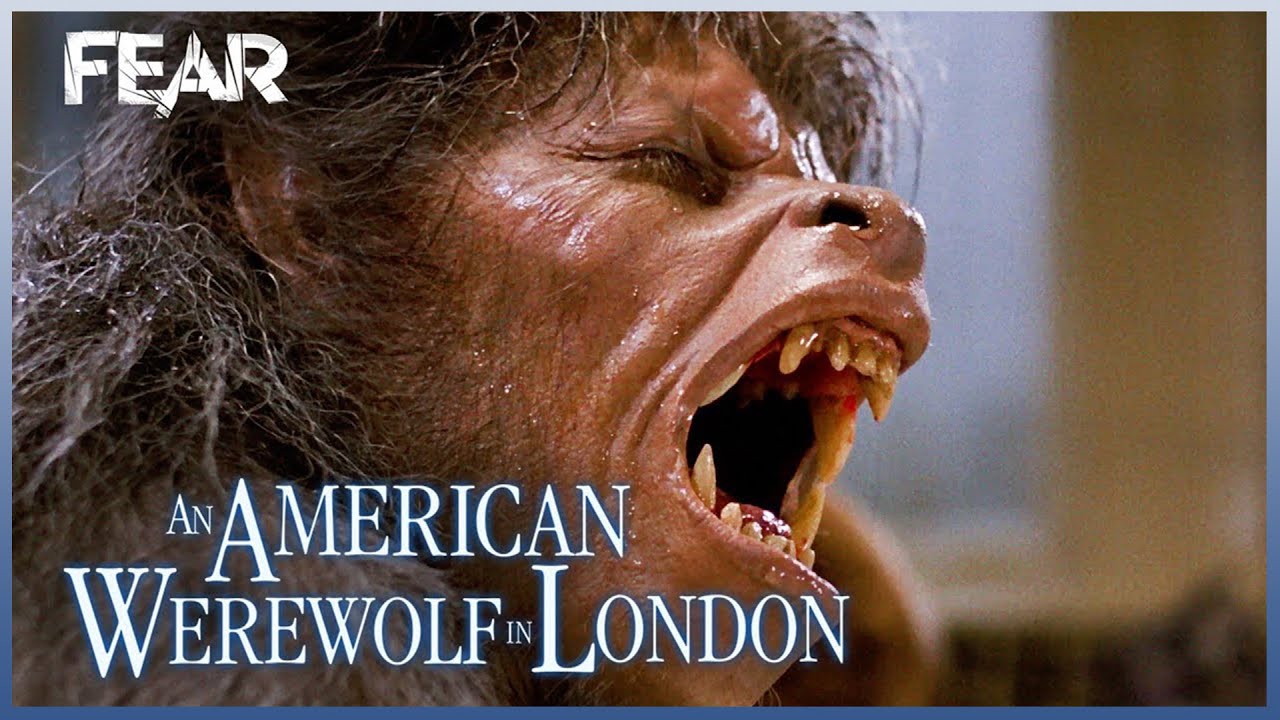

With that said, it is my opinion that creature-FX hardly ever really works that well, if they try to do it practically. A guy in a suit (think ‘Alien’) is a guy in a suit.

And something like that scene from ‘Star Wars Episode IX’, where that one little alien-creature is doing repairs on C3-PO’s head, well, I think it looks pretty cringeworthy. You can tell from a mile away it’s a small pupett made from latex, because something is always wrong about the SSS or something with these and also because it just doesn’t move like a life organic beeing at all.

Now I’m kind of not feeling like typing much more or thinking of/searching for other examples of where practical FX, works well or where it falls short or where either of the two is to be said about post FX and CGI, so I leave the discussion to you.

greetings, Kologe